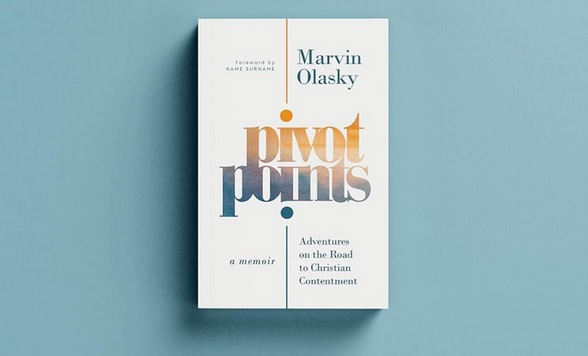

IN life’s transitions, breaking free from fear necessitates either an immense ego or unwavering faith in God. A bloated ego urges us to grasp for what isn’t rightfully ours, while genuine contentment begins with trusting in God. Marvin Olasky’s sequel to “Lament for a Father” chronicles his journey from Judaism to atheism, then Marxism, and ultimately finding solace in Christ. Through his experiences in evangelical, conservative, compassionate, and journalistic circles, he offers a rich perspective on faith and navigating life’s changes.

The following is an excerpt from Marvin Olasky’s new book, “Pivot Points: Adventures on the Road to Christian Contentment, A Memoir.”

THE other part of my plan is to get a PhD, aided by a fat fellowship from the University of Michigan. In August 1973, my wife flies back to Oregon, and I bus to Ann Arbor. I’ll study American- Soviet relations, continue learning Russian, and become a Moscow correspondent. In September my room in a boarding house just west of the U of M campus sports a single bed, a night table bearing an alarm clock and a lamp, a red upholstered chair, and two folding chairs.

My bookcase, made from flattened cardboard boxes and bricks, displays not only Marx, Engels, and Lenin, but Herbert Aptheker’s American Negro Slave Revolts and three volumes by Bulgarian Communist boss Georgi Dimitrov. The two heads of the Michigan Communist Party soon visit me. They may be amused — Bulgarian Communism! — but they do not sneer at my books as did the Yale committee. They flatter me and suggest I bring to campus Georgy Arkadyevich Arbatov, the fifty-year-old director in Moscow of a Soviet think tank, the Institute for US and Canadian Studies.

University officials are enthusiastic about the idea. So am I, because Arbatov can facilitate my return to the Soviet Union. The two Communist Party leaders promise to help. Soon, a letter from Moscow arrives with Arbatov’s acceptance of the invite. Meanwhile, corrupt vice president Spiro Agnew resigns as Watergate explodes the Nixon administration. Capitalism is destroying itself, and I’m on the winning side!

Life is good. Michigan professors love my Marxist analyses. I plan to stay at U of M and get a PhD. The university library subscribes to Pravda, the Moscow newspaper. My Russian knowledge is good enough for me to read about “unyielding war against religious patterns of thought.” I’m an addict who favors “suppressing, once and for all, of those relics from the past,” as Pravda puts it.

On Halloween, students in Nixon masks stalk the Diag, the walkway cutting across the central section of the University of Michigan campus. The next day, November 1, 1973, begins as normal with my reading of Pravda in the library. Then I offer Marxist views in a literature class, eat hamburgers in the dining hall, and am back in my room just before 3 p.m. to sit in my red chair by the window and read Lenin’s famous essay “Socialism and Religion.”

I’m feeling on top of the world, in line with Lenin’s belief that religion is “opium for the people. … Spiritual booze in which the slaves of capital drown their human image.” Lenin argued often that God is a “figment of man’s imagination,” so Communists “must combat religion — this is the ABC of all materialism, and consequently Marxism.”

Suddenly, without warning, on an ordinary day, figment becomes fact. New thoughts bombard my brain: What if Lenin is wrong? Why am I sure that God does not exist? Why have I turned my back on him? Mixed up in that is a sense that it’s bizarre to hate America and love Russia, since my own grandparents came to the exactly opposite conclusion.

For eight hours I sit in that chair, unwilling to move. Every hour brings a glance at the clock and surprise that I am still stationary. It’s hard for me to convey the strangeness, the otherness, of this experience. No drugs, no dreams, just sitting in the chair, hour after hour, suddenly thinking Marxism is wrong. At three o’clock I’m an atheist and a Communist. At eleven p.m. I’m a believer in a God of some kind. Hardly born again, but no longer dying.

At eleven, finally, I stand up, go outside, and wander around the cold and dark campus for the next two hours, trying to make sense of those eight hours. I can’t figure it out immediately. Years later I read in the Westminster Confession of Faith that God “is pleased, in His appointed and accepted time, effectually to call [some] by his Word and Spirit out of that state of sin and death in which they are by nature, to grace and salvation by Jesus Christ.”

Sometimes that happens all at once. Sometimes that takes years. Sometimes, as in my case, part happens all at once and part is a slow train coming. My faith in Communism is gone, so after three days it seems right to visit the University of Michigan law student who heads the Communist Party chapter in Ann Arbor. I tell him I’m out. He denounces me as “a bourgeois individualist” and uses other ideological expletives.

For the next three weeks, I still go to the university library, this time to read not Pravda but books by former Communists. The most helpful is Witness, published in 1952. In it, Whittaker Chambers describes the Communist vision that attracted him in the 1920s and me decades later: “It is not simply a vicious plot hatched by wicked men in a sub-cellar. … It is, in fact, man’s second oldest faith. Its promise was whispered in the first days of the Creation under the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil: ‘Ye shall be as gods.’ It is the great alternative faith of mankind.”

Chambers writes, “The Communist vision is the vision of Man without God.” But what God? I’m long gone from Judaism, most of which no longer emphasizes personal experiences with God. And aren’t Christians stupid people who worship Christmas trees?

So I drift. My first, temporary harbor is theistic existentialism, starring Søren Kierkegaard in the nineteenth century and Gabriel Marcel in the twentieth. God exists, so even though our world is broken, hope remains. But within such thinking, the nature of God is such a mystery that we cannot really know him or what he wants us to do. Within such thinking, right and wrong are subjective — and I’m not willing to settle for that.

A second harbor, and one in which I linger, is free-market economics, with Henry Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson my first reading and Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom a sacred scroll. Through much of 1974 and 1975, grateful for deliverance from my Moscow addiction, I identify with libertarian conservatism. And yet, during each six-month period during those two years, a new challenge to that direction emerges.

Spring semester 1974. Although my primary reason for studying Russian is gone, I still need a reading knowledge of a foreign language to gain a PhD. My childhood Hebrew and high- school French are distant, so one night for reading practice I pluck from my cardboard shelves a copy of the New Testament in Russian that comes from a Russian- speaking commune in Oregon. In my frugal way I’ve held onto it because paper does not grow on trees.

I begin at the beginning, the Gospel according to Matthew. Chapter 1 is easy, as Abraham begets Isaac and other begats lope down the page. The next three chapters — filled with wise men, Herod’s baby massacre, John the Baptist’s fury, and Jesus’s joust with Satan — are exotic enough to hold my attention, with a Russian-English dictionary in front of me.

The Sermon on the Mount in chapters 5 through 7 gets to me. Some Communists murder. Others stop short of that, but all are pro-anger, devoted to fanning proletarian hatred of The Rich. They are two- eyes-for-an-eye. Josef Stalin’s method of dealing with opponents — nine grams (a bullet) to the back of the head — was only a slight outlier.

Jesus, though, is not only anti- murder but anti- anger: “Everyone who is angry with his brother will be liable to judgment.” Such lofty standards are a mystery, and I wonder if anyone can meet them. The Sermon is so striking that the Bible seems to be from God, not from man.

Fall semester 1974. As a PhD student, I have to teach a class at some point during my graduate school career. None of the regular professors wants to teach Early American Literature, so that becomes my assignment, even though I’ve never studied it. Starting in July, I cram by reading Puritan sermons, including ones by John Cotton and Increase Mather. I annotate my copy of Perry Miller’s anthology The American Puritans with red underlinings and marginal notes about “God’s way” and “grace.” That paperback, still on my bookshelves, undermines my prejudiced belief that “Christian thinker” is an oxymoron.

The sermon with the most underlining is Thomas Hooker’s “A True Sight of Sin,” which certainly describes people like me who think that “to please [their] own stubborn crooked perverse spirit is a greater good than to please God.” Hooker nails my assertion of autonomy: “I will be swayed by mine own will and led by mine own deluded reason and satisfied with my own lusts.”

But it’s Ann Arbor, college town! I like my delusions and lusts.

Spring semester 1975. Having taught an assigned course in fall 1974, I now get to make up my own. My course is on Western movies with tragic undertones. Sure, many cowboy movies are for kids, but every week during the semester the students and I watch an adult Western from the 1948–62 era that focuses on character. The heroes don’t always triumph in the end, but they are unbribed, self-controlled, prepared to sacrifice themselves for others, and quiet yet exploding into action when necessary. They show — to apply philosopher William James — “the profounder way of handling the gift of existence. Naturalistic optimism is mere syllabub and flattery and sponge-cake in comparison.”

Some research shows me that Communist screenwriters in Hollywood during the 1930s and early 1940s liked to work on Westerns so they could put themes of class struggle (small farmers versus big ranchers) into the minds of moviegoers when their political guards were down. This insight — same approach as my Boston Globe writing about immigrants and farmers — leads to a research question worthy of a dissertation: How do Westerns from the 1930s to the 1970s reflect the left- right debates dividing the United States during that era?

Once summer starts, a travel grant for dissertation research helps me to spend a month in Washington, DC, each day watching four obscure Westerns at the Library of Congress. (No Blockbuster or streaming services then.) Then it’s off to Los Angeles to interview aging screenwriters excited that someone in 1975 remembers them. One is less thrilled when he picks me up at my hotel room near Skid Row (twenty-one dollars per week for the room) and finds the scholar who appreciates his work wearing an off-white leisure suit picked up for a few dollars at Filene’s Basement in Boston, famed for discounts.

Fall semester 1975. On Friday, August 22, I’ve just moved into my new basement apartment at a rooming house a block away from the University of Michigan campus. Rent is a bargain at $180 per month, with $40 off that because I’m replacing a young couple that’s been doing minor management for the owner, including collecting and passing out keys. My apartment has a gerbil cage and two gerbils, with the wall decorated by a hula hoop hanging on a nail.

The doorbell rings. Standing there is a fresh-faced young woman wearing an uncertain smile.

“Pivot Points: Adventures on the Road to Christian Contentment, A Memoir” is available now online.